News

26 October 2013

The Right to Food: progress and limits

In his Newsletter dated 25 October, Olivier de Schutter summarises the conclusions of the report he has just submitted to the UN General Assembly. This report takes stock of the ‘‘impressive’’ progress made by countries in adopting laws, policies and strategies for implementing the Right to Food.

In his press release, O. de Schutter stresses three types of progress:

-

•Countries like South Africa, Kenya, Mexico, Côte d’Ivoire and Niger that have given direct constitutional protection to the Right to Food, and those like El Salvador, Nigeria, and Zambia where reform processes are underway

-

•Countries like Argentina, Guatemala, Ecuador, Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Honduras, where Right to Food framework laws, often taking the shape of 'Food and Nutrition Security' laws, have been adopted and several other Latin American countries that are in the process of adopting similar measures.

-

•Countries including Uganda, Malawi, Mozambique, Senegal and Mali that have adopted, or are in the process of adopting, framework legislation for agriculture, food and nutrition that enshrines rights-based principles of entitlements and access to food.

The report also gives several examples of legal decisions that have resulted from these measures (ensuring the socio-economic rights of small-scale fishers in South Africa; ruling by the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights and the ECOWAS Court of Justice on Nigeria’s policy towards the Ogoni people; the decisions taken to develop certain social programmes in India and to provided food assistance in some neglected regions of Nepal and Argentina).

Finally, the report also stresses the critical role played by civil society and some parliamentarians sometimes grouped as in the case of the Parliamentary Front against Hunger in Latin America.

O. de Schutter’s report provides many examples and shows that things have been changing in favour of the Right to Food during the last decade. However, regrettably, the report does not provide an exhaustive picture of the situation with respect to the implementation of the Right to Food. This picture is difficult to assemble but it would help to see whether the progress reported by O. de Schutter translate themselves effectively in an improvement of the food situation in the countries concerned. This monitoring, information collection and evaluation work appears indispensable and should be conducted systematically.

Below is a first, rough and imperfect attempt which however helps to gather some important elements.

If one gathers the data from the report and those available on the FAO website, it is possible to make a list of countries where the Right to Food is recognised by the Constitution and check how their food situation evolved over the years. It appears that 24 countries are concerned. They are: Bangladesh, Brazil, Colombia, the Congo, Cuba, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Haiti, India, Islamic Republic of Iran, Malawi, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Paraguay, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Uganda and Ukraine.

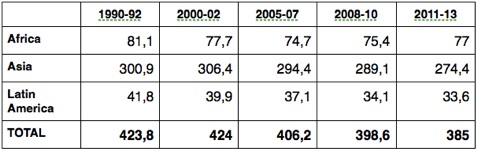

The two tables below describe this evolution taking as reference the data published by FAO (The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013).

Evolution of the number of undernourished people living in countries where the Right to Food has been recognised by the Constitution (1990-2013, in million persons)

Source : author’s computations based on FAO 2013 data

N.B.: no data for Cuba, Iran, Mexico, South Africa and Ukraine

Evolution of the proportion represented by the undernourished people living in countries where the Right to Food has been recognised by the Constitution in the total number of undernourished people in the world (1990-2013)

Source : author’s computations based on FAO 2013 data

N.B.: no data for Cuba, Iran, Mexico, South Africa and Ukraine

What can be derived from these two tables?

-

•The number of undernourished people living in countries where the Right to Food has been recognised by the Constitution has been reduced during the last ten years. This reduction is strong in Asia and Latin America, but only marginal in Africa

-

•Globally, at world level, this reduction has been slower than in the rest of the word, except in Africa where hunger has been increasing in those countries that have not recognised the Right to Food in their Constitution. This is particularly true in Latin America which however has been the most advanced region with respect to the Right to Food.

These conclusions are surprising at first. They raise two critical questions:

-

•If the recognition of the Right to Food is not sufficient to translate itself in a rapid reduction of the number of undernourished people, is this due to the fact that it is often not really enforceable in Court and has not led to the implementation of programmes aiming at reducing the number of people suffering from chronic hunger?

-

•The limited impact of the recognition of the Right to Food is it due, as seems to be suggested by some of the examples shown in O. de Schutter’s report, to the fact that at present this recognition mostly results in actions in the case of crisis or emergency situations when the victims of hunger are clearly visible and their lives are threatened in a spectacular way?

Let’s hope that the Special Rapporteur, FAO or any other organisation with the capacity to undertake this work will establish a Right to Food monitoring system that will provide answers to this type of questions and suggestions on how to adjust the work to promote this fundamental right to make it even more effective.

Last update: October 2013

For your comments and reactions: hungerexpl@gmail.com