News

25 August 2016

European Companies and Land Grabbing: evidence of human rights violation

When the world became conscious of Land Grabbing, the tendency was to point at countries like the Gulf States, China or South Korea as the main culprits. A recent report prepared for the Directorate-General for External Policies of the European Parliament shows that EU-based companies have been extensively involved in land grabbing and guilty of violation of human rights.

The report, ‘Land grabbing and human rights: The involvement of European corporate and financial entities in land grabbing outside the European Union’ prepared by a group of specialists from the International Institute of Social Studies in the Netherlands and of FIAN-Germany (For the Right to Adequate Food) gives evidence of the involvement of EU-based corporate and financial entities in land deals occurring outside of the EU. It analyses their impact on communities living in areas where the investments are taking place and points at strong shortcoming in the EU’s reaction to human right challenges in the context of land grabbing. It also shows that ‘business self-regulation and corporate social responsibility schemes are insufficient and inadequate for addressing human rights issues in the context of land grabbing’. It concludes by stating that ‘The multi-layered character of land grabs, the involvement of different EU actors, and the different mechanisms of land grabbing require a set of regulatory actions by different bodies in the EU and its [Member States]’.

Within the complexities of land grabbing processes and the intricacies of investment webs, the Report identifies five key mechanisms through which land grabbing occurs and that need to be well understood to tackle properly the human rights challenges they generate:

-

•‘EU-based private companies involved in land grabbing through various forms of land deals;

-

•Finance capital companies from the EU, including public and private pension funds, involved in land grabbing;

-

•Land grabbing via public-private partnerships (PPPs);

-

•EU development finance involved in land grabbing; and

-

•EU companies involved in land grabbing, which are taking advantage of EU policies and gaining control of resources through the supply chain.’

Concrete examples are presented in the report to illustrate each of these mechanisms.

It also shows that ‘while land grabbing that expels people from the land is a common occurrence, it is not necessarily the only path in which central states and corporations pursue resource 'control grabbing' wherein possible human rights violations and abuses can occur’.

It makes distinction among four contexts within which human rights can be violated:

-

-People are expelled from their land;

-

-People are hired to work on the land, but under exploitative conditions;

-

-People are barred from having access to their land because of land deals that block access (e.g. their land can be landlocked in new plantations resulting from land deals);

-

-People have long been expelled from their historical land and have become marginalised, and their right to regain access to their land is not recognised.

Here too, for each context, precise examples are given.

Adopting this broad approach suggests that land grabbing is a much more important phenomenon that what had so far been thought, for example if it is approached through the data available in the Land Matrix [see our article ‘Land: an unequally distributed, threatened but essential resource’, section on land grabbing] and also includes land under REDD arrangements [read our article Forests: rural communities caught between markets and the objective of conserving the planet, section on ‘‘Carbon’’ concessions].

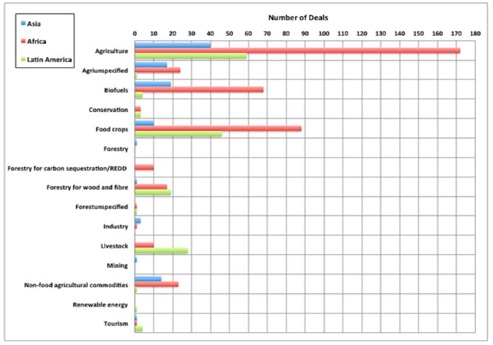

Based on this, the report states that EU-based companies have been involved in 323 deals affecting 5.8 million hectares, of which 60% in Africa, 26% in Latin America and 14% in Asia.The two top-most involved countries are the UK (124 deals, 2,0 million hectares) and France (40 deals, 0.6 million hectares).

But actual involvement through investment webs can be much more important. For example, according to a 2010 study quoted by the report, DWS the German investment fund had funded companies that control more than 3 million hectares, while estimates of German involvement in land grabbing usually mention a figure of 0,3 million hectares only. Other cases presented in the report show that land grabbing is sometimes performed by companies who benefit from support from aid agencies (see example of Toronto-based Feronia Inc. that benefitted more or less directly from funds or support, among others, provided by bilateral and multilateral African development finance institutions, IFAD, UNIDO, AGRA, UK’s DFI, the Italian Development Corporation, France’s AFD (Proparco), AfDB, and many other European aid agencies or development banks).

The report also mentions cases of violence against opponents to EU company-backed projects that have involved the killing of activists (e.g. the case of Berta Cáceres and Nelson García in Honduras, Feronia in DRC, Marlin in Guatemala, murders of Guarani-Kaiowá people in Brazil, etc.)

The report also reviews EU’s response to land grabbing and concludes by making a series of recommendations on how the EU can have ‘a role to play to stop land grabbing and actively address related human rights violations and abuses’. In particular, it advocates, among others:

-

•A series of regulatory measures that are designed to tackle the root causes of the problem like:

-

-

•Adjustment of human rights clauses in trade and investment agreements

-

•Allowing for complaints by individuals and groups whose human rights have been negatively affected

-

•Systematically carry out prior human-rights impact assessments

-

•Implement human rights impact assessments by both the European Parliament and the Council

-

-

•Dropping the biofuel target and exclude bioenergy from the next EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED)

-

•Withdrawing support of the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in Africa

-

•Supporting the implementation of the Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land Fisheries and Forests produced by the CFS

-

•Establishing a registry at EU level of all EU actors involved in land deals abroad

-

•That EU members have to ensure victims' access to effective judicial remedies, including by assuming jurisdiction in cases of corporate human rights abuses committed by EU-based actors

-

•Continuing and scaling up support/protection for human rights defenders

-

•The production of a toolkit on land grabbing for staff in the EU headquarters, EU Member States’ capitals, EU Delegations, Representations and Embassies.

It will be interesting to see how seriously these recommendations are implemented in the near future and to what extent they will succeed in stopping the involvement of EU-based corporate and financial entities in land grabbing.

————————

To know more:

-

-Directorate-General for External Policies of the European Parliament, ‘Land grabbing and human rights: The involvement of European corporate and financial entities in land grabbing outside the European Union, 2016

Earlier articles on hungerexplained.org related to the topic:

Last update: August 2016

For your comments and reactions: hungerexpl@gmail.com