News

21 October 2023

download pdf file: MIgration2023_eng.pdf

Four myths about migrations…

Five years ago, one of our articles presented briefly “(The minimum of) What you should know about migration…” [read].

In 2023, we would like to debunk four myths that are repeated relentlessly and bias the debate around migrations.

First myth: Rich countries are threatened by massive migration of the poor of this world

In 1989, French Prime Minister Michel Rocard stated in front of the National Assembly that “even if like you I regret it, our country cannot welcome and alleviate all the misery in the world, we must mobilize the means that this requires” [read in French]. This phrase was used extensively in France to support the myth that all the poor in the world would invade rich countries, in particular France.

But how do migrations really take place in the world?

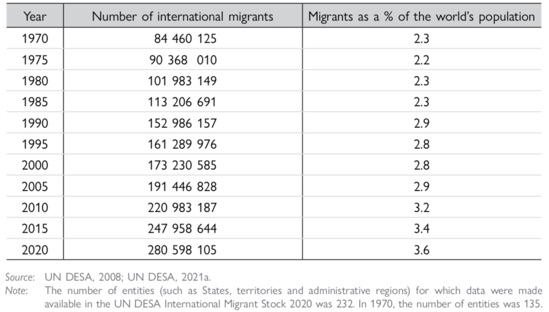

It is quite clear that international migratory flows have been rapidly increasing, as shown by the latest “World Migration Report 2022” [read] of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The total number of migrants in the world has more than tripled, moving from 85 million people to more than 280 million people in 50 years (Table 1).

Table 1 - International migrants (1970-2020)

Source: IOM, 2021

To these data on international migrations, one should add those dealing with internal migrations that are much larger according to researchers, particularly those resulting from the urban drift that is still taking place in middle- and low-income countries. These migrations can be huge. At the start of this century, the UN declared that the figure of 740 million people that had been proposed for internal migrations was “conservative” [read]. In China, for example, urban population grew from 18.5% of total population in 1980 to 59.58% at the end of 2018, as stated by the National Bureau of Statistic of China, quoted by Losavio [read in French]. This corresponds to a minimum of several hundred million people moving over the period within the country.

Proportions comparable to those between international and internal migrations can also be observed for displaced people. At the end of 2020, IOM estimated that there were 89.4 million displaced people in the world, of whom 55 million people were displaced in their own country (48 million because of conflicts and 7 because of disasters) (p. 4 of the IOM report).

Paradoxically, most of the research work and studies deal with international migrations, while internal migrations remain poorly documented and analysed.

According to the IOM report, in 2020 the US were, by far, the country of destination where the largest number of international migrants were found (50 million people), followed by Germany and Saudi Arabia. India was the country from which the largest number of international migrants originated (close to 18 million people), followed by Mexico and Russia (IOM report p. 25).

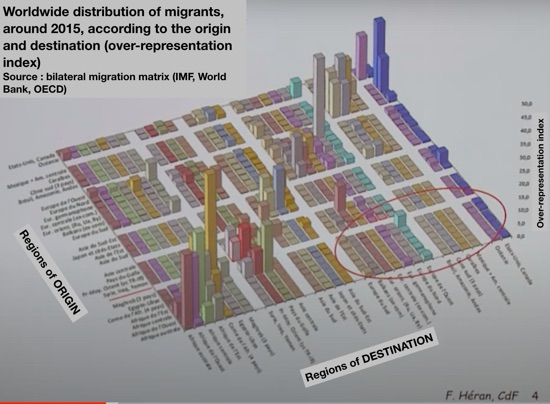

The analyses made by Héran on the basis of data available in the bilateral migrations database (World Bank) tell us that:

-

•Almost 30% of international migrants, in 2015, had migrated within their region (70% for Sub-Saharan Africa, compared to only 1% in North Africa) [read in French p. 2].

-

•The analysis of the distribution worldwide of migrants according to their origin and destination by region, based on the over-representation index, shows very remarkably that the migrants remained overwhelmingly within their originating region, with some notable exceptions, particularly the Maghreb for which migrants mostly settled in Western Europe (see Graph 1. area circled in red in the south-east corner of the diagram).

Graph 1 - Worldwide distribution of migrants, around 2015, according to the origin and destination

(over-representation index)

Source: Héran, Cours au collège de France, 2018 [watch in French]

(translated by hungerexplained.org)

-

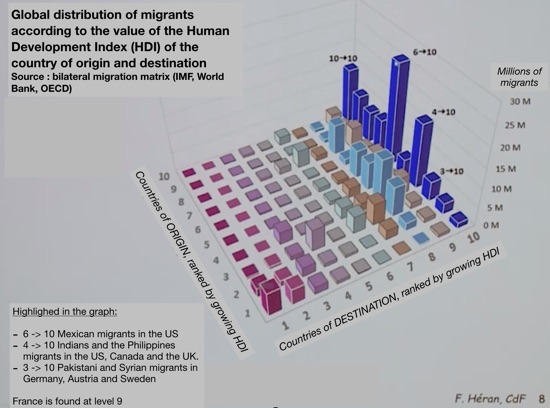

•The analysis of the global distribution of migrants according to their origin and destination among groups of countries established on the basis of the value of their Human Development Index (HDI) also shows that people from poor countries migrate mainly towards other poor countries, and that the bulk of migrants in high-HDI countries (North America and Europe) originates from countries with a middle-level HDI value. Typically, Mexicans migrate to the US, people move from India and the Philippines to the US and Europe, and people from the Middle East go to Europe (see Graph 2).

Graph 2 shows clearly that the largest number of migrants is located in the “North-Eastern” corner of the diagram, meaning that migration is mostly taking place between countries with a middle-level HDI towards to countries with a high HDI, while migration from low HDI countries towards high HDI countries is only a small part of migrations.

With some humour, Héran notes the very different ways in which “migration” and “expatriation” are presented - despite both being basically the same thing - the latter being qualified very positively as “an adventure”, as a means of “acquiring experience” and “discovering new cultures”…

As a result of this analysis, it appears therefore that the “misery in this world” migrates among poor countries, contrarily to what we are continuously being told!

Graph 2 - Global distribution of migrants according to the value of the Human Development Index (HDI) of the country of origin and destination

(in millions)

Source: Héran, Cours au collège de France, 2018 [watch in French]

(translated by hungerexplained.org)

Moreover, it is important to note that migration towards the richest (and furthest away) countries is largely unaffordable for the poorer population groups, including in middle-level HDI countries. Resources are needed to migrate, and more and more, a high level of education and qualification is required to be welcome in a growing number of countries that are adopting a selective immigration policy. Resources and education, however, are two factors that are cruelly lacking in the poorest countries, and even more in their most disadvantaged population groups.

This myth is therefore doubly wrong!

Second myth: Demographic growth is the main cause of international migrations

The doomsayers of migration swamp us with messages warning us of an invasion by swarms of ragged migrants landing on our shores, pushed by rapid population growth.

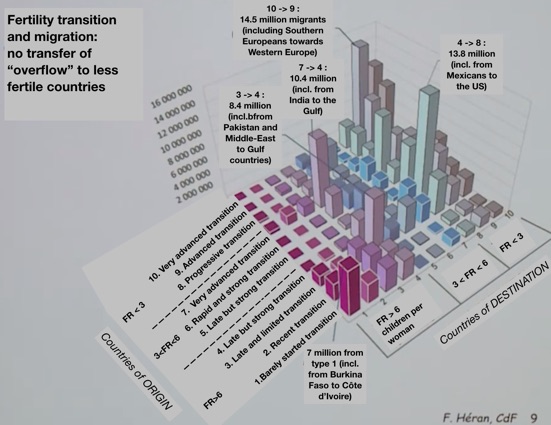

This is also a myth, as shown by the analyses made by Héran in Graph 3 below.

Graph 3 - Demographic transition and migration

(FR = fertility rate = number of children per woman)

Source: Héran, Cours au collège de France, 2018 [watch in French]

(translated by hungerexplained.org)

Graph 3 shows that, in reality, people from countries where population is growing fast migrate relatively less than those from other countries, and that they migrate mostly to countries similar to theirs from the demographic point of view. On the contrary, the population of countries where demographic transition is well advanced and where the number of children per women is lower, migrates relatively more than others.

The exception is of those countries where the demographic transition is still at its beginning but that are rich in resources (mainly Gulf countries that attract migrants from Pakistan and India).

Therefore, population growth is not the driver of migrations that some would want us to believe.

Third myth: The main cause of international migrations is the « suction effect » created by very generous social protection benefits offered in destination countries

In Europe, especially in France, some political leaders are continuously repeating that immigrants are attracted by generous social protection benefits and free medical care.

However, it is sufficient to simply consider the list of countries that are the ten most important destinations of international migrations (see IOM report, p. 25), to find that in the list, there are 4 very well placed countries that are not particularly known as social paradises:

-

-

•the United States (1st, with more than 50 million migrants);

-

•Saudi Arabia (3rd, around 15 million);

-

•the Russian Federation (4th, a little over 10 million);

-

•The United Arab Emirates (6th, slightly less than 10 million).

-

-

From these figures, it is impossible to conclude that social benefits are the main driver of migrations.

Note that the 6 other countries among the 10 top destinations are: Germany (2nd), the United Kingdom (5th), France (7th), Canada (8th), Australia (9th) and Spain (10th).

Fourth myth: Economic development in emigration countries is the best way to reduce migration flows

Another popular idea in countries wishing to reduce immigration is that economic development in emigration countries would help cut migration flows.

The very idea that migration flows should be lessened may be very much challenged. In general, the most forceful opponents to immigration justify their view by the need to preserve their national identity. Strangely enough, they do not mobilize against the many other processes, sometimes much more effective, that modify our culture by creating contact and exchanges with other cultures, such as movies, literature, music, internet, tourism, etc., not to mention paid influencers of all sorts who seek to change in depth our way of being and (primarily) of consuming…

This fourth myth is as wrong as the preceding three, particularly so in the case of Africa which, for those who promote this idea, is the region from where immigration is supposed to be the most “dangerous” (one can detect racist undertones in this position).

Two researchers, Flahaux and De Haas, who specialize in the study of migrations, contradict the conventional explanations of migration out of Africa and the usual clichés that support them. They think that rather than “driven by poverty, violence and underdevelopment, increasing migration out of Africa seems rather to be driven by processes of development and social transformation which have increased Africans’ capabilities and aspirations to migrate”. This, according to the authors, is “a trend which is likely to continue in the future” as a consequence of easier access to information, media and publicity that “change people’s perceptions of the ‘good life’” [read].

This thesis is quite consistent with the data showing that the largest flows of international migration occur between middle- and high-income countries, as seen when discussing in this text the first myth (see in particular Graph 2 above).

It also rests on the fact observed by researchers and quoted by Flahaux and De Haas that “most Africans migrate out of the continent in possession of valid passports, visas and other travel documentation”.

In short, with a better education and more resources, it becomes much easier to migrate, to satisfy one’s ambitions and to find a well-remunerated job in a richer country, thus escaping the penalty of the unjustified salary difference existing between a worker living in a rich country and one living in a poor country, at comparable qualifications and productivity levels [read pp. 2-5].

The idea that education, training and economic growth are contributing to increase emigration should be no surprise to us, unless we suffer from a short memory and have forgotten the fundamental role these three drivers played in the process of rural-urban migration in rich countries, especially in Europe. They have been instrumental in easing the migration of baby boomers and their successors out of the countryside towards cities and their new and multiple jobs, particularly during the “Glorious Thirty”.

Could Africa and Africans be so different for the same causes not to create the same effects? There is no evidence to suggest they are. Provided, of course, that job opportunities develop in urban areas, sufficiently to generate every year millions of positions for the new generations and that with society getting richer, qualifications of the labour force will further improve. And that is where, for the time being, facts are not really so encouraging.

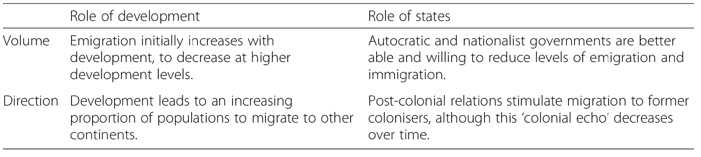

Table 2 sums up the thesis proposed by Flahaux and De Haas on the basis of their analysis of the available data.

Table 2 - Dimensions of analysis and theory-derived ideas

on migration determinants

Source: Flahaux and De Haas, 2016

More generally, as long as, at comparable qualification and productivity, salaries in middle- and low-income countries will remain lower than in high-income countries, international migrations will persist to grow, whatever immigration policies are adopted.

Conclusion (provisional)

As can be seen, migrations are no simple processes! And they raise many questions and are the source of many and lasting myths, most often for unmentionable motives.

More research is needed on migration whether international or internal. They will provide arguments required to try and debunk myths that will not fail to appear in this particularly sensitive field.

——————————

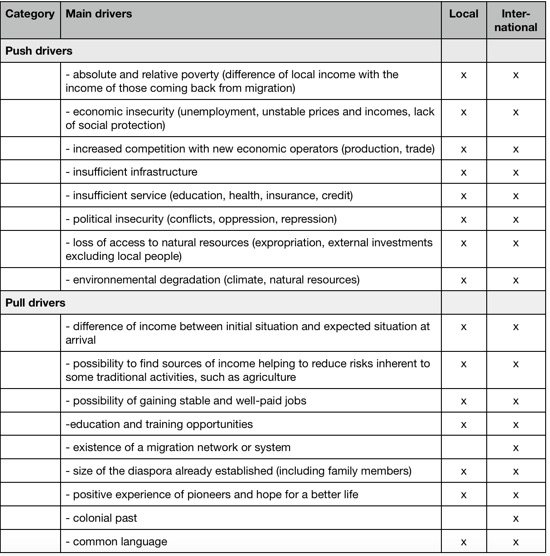

Annexe: drivers of emigration in conventional literature

The following table presents a summary of the main drivers of emigration that are found most frequently in the conventional literature on this topic. It makes the difference between the “push” and “pull” drivers of emigration.

It can be seen that drivers are almost the same for local and international migration. There are many obstacles to migration. They are more difficult to overcome in the case of international migrations as demonstrated by the many migration tragedies, particularly in the Mediterranean Sea.

---------------------

Notes

-

1.The precise (and complex) definition of an international migrant can be found on p. 341 of the IOM report.

-

2.See for example work by Keldon [read] who raises the many problems posed by statistics on both international and internal migrations.

-

3.Flahaux and De Haas [read] found, however, that intra-African migrations are declining, while a more diversified migration develops towards other regions, in particular Europe, North America, the Middle East and Asia.

-

4.The over-representation index is computed by the ratio of the share of migrants from a particular region in total population divided by average of the shares of all regions.

-

5.The HDI is a composite index (value between 0 and 1) per country, computed from data on health and life expectancy, level of education and income level.

————————————-

To know more:

-

•McAuliffe, M. and A. Triandafyllidou (eds.), World Migration Report 2022. International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva, 2021.

-

•Losavio, C., Les migrants de l’intérieur en Chine : processus de catégorisation et enjeux analytiques, Perspectives chinoises 2021/2, 2021 (in French).

-

•Héran, F., Pourquoi migrer ? Théories de la migration : la modélisation des causes, Collège de France, 2019 (in French).

-

•Héran, F., L’Europe et le spectre des migrations subsahariennes, Population & Sociétés 2018/8 (N° 558), INED éditions, 2018 (in French).

-

•Skeldon, R., International Migration, Internal Migration, Mobility and Urbanization: Towards More Integrated Approaches, Maastricht University, 2017.

-

•Flahaux, ML. et De Haas, H., African migration: trends, patterns, drivers, Comparative Migration Studies 4, 1, 2016.

Selection of past articles on hungerexplained.org related to the topic:

Last update: October 2023

For your comments and reactions: hungerexpl@gmail.com