Opinions

Download pdf file Lampedusa.pdf

Lampedusa, Westgate and Famine in the Horn of Africa

It’s All too Easy to Forget

When an overloaded boat capsizes near the shores of Lampedusa, and hundreds of coffins are lined up in neat rows in a huge hangar, we feel the same emotions of shock, sadness and pity as those that struck us ten days earlier when around 70 innocent shoppers were shot and killed in Nairobi’s Westgate Mall. For a few days, the world’s media focussed on these events and then they vanished from the front pages and television screens almost as quickly as they appeared. And, unless we have been close to one of the victims, our own memories of these horrific scenes will quickly dim as we go about our normal lives.

This capacity to consign bad memories to the recesses of our minds may protect us from the insanity that would surely overwhelm us if we retained vivid images of all the horrors that afflict humanity.

The ability to forget, however, is not just individual but unfortunately also has very disturbing institutional dimensions.

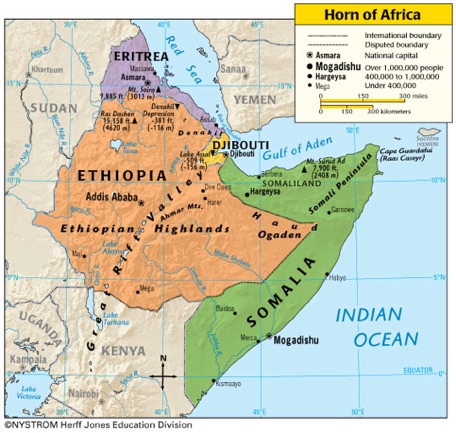

Most individuals and institutions have already conveniently forgotten that a quarter of a million Somalis died from hunger – in a world awash with food – in the famine that struck them just two years ago. And, if the massive 1984-85 Ethiopian famine is remembered at all, it is more because of Geldof and Bono than because of those who died. Since then, every 5 to 10 years there has been a serious food emergency in the Horn of Africa which has displaced millions from their homes and triggered a disaster relief effort on a massive scale, but usually, as was the case recently in Somalia, too little, too late. These emergencies, too, it seems, have been easily forgotten.

Each successive emergency has led to “never again” statements of intent by governments in the region and the “international community”, with promises to get to grips with the underlying problems that lead so many people to be exposed to recurrent risks of famine. But, once the disaster has passed into history, the tendency has been to return to “business as usual”. In the Horn of Africa, good early warning capacities have been created and two countries have put in place large-scale social protection programmes, but, otherwise there has been little concerted action to improve the livelihoods of those who are most vulnerable to the shocks to which the region is so prone..

Because they saw a bleak future for themselves at home, the people who drowned at Lampedusa had taken the huge risk of trekking from the Horn of Africa for thousands of miles across some of the harshest lands on Earth. And then they paid all that they owned to board an over-crowded boat to the promised shores of Europe. It was an act of desperation. You can blame the people-smugglers for the loss of life, but the real cause is back home – the threat of a lifetime of constant deprivation, a life “on the edge”.

It is easy to brand those Somalis and their sympathizers who burst into the luxury Westgate Mall with grenades and Kalashnikovs as “terrorists”, but they, too, deliberately chose to risk their lives for their beliefs. While not condoning such brutal acts, I see them being born out of the same kind of despair and sense of hopelessness – and of injustice - that drives others to risk everything to seek a better life in far-off countries. It is no coincidence that almost all recent conflicts have taken place in countries and regions affected by protracted crises. Conflict thrives where life is cheap.

But these two events serve as a timely reminder that we live in an increasingly interconnected world in which growing - and hugely visible – inequalities are bound to trigger greater waves of migration and destabilizing conflicts. As now, these will have their origins amongst the most deprived of all our fellow humans, those who live under the threat of some kind of disaster – set off by disputes over access to land and water, drought, floods, pests or the low prices for what farmers produce.

And so I hope that the global institutions that share responsibility for reducing poverty and hunger and the governments that fund them will take these grim events - and others that are sure to follow - as reminders of the need not to wait for fresh disasters to strike before they act but to invest massively now in helping vulnerable communities to build their own resilience to the very real threats that face them.

There is fortunately no longer an official state of famine in Somalia but millions of people are still on the very brink of survival. It is good to see that FAO and its partners are working hard with many of these and similarly exposed people in neighbouring countries to ensure that they have the means to eat adequately and thus will be able to stand on their own feet even when times again get difficult. But the scale of action remains small because the international community still needs to be persuaded that it is not just a matter of justice and fairness but also in their own self-interest to deepen and sustain their commitment to resilience building rather than wait for the next disaster to strike, whether in the Horn of Africa, the Sahel or Central Africa.

I am sure that most of us who visit this site are committed to the idea that nobody now living should ever again face the threat of famine. But we also know that the risk of famine cannot be removed through the repetitive last-minute scrambling of emergency aid. We must call for a move upstream, focussed on creating the prospect of a healthy and dignified life for all people free of the threat of hunger and malnutrition, and assuring that hard-won assets are protected at times of crisis.

Perhaps the time has come to talk to those we now brand as “terrorists” or “opponents” – and we may be surprised (as I was when consulting UNITA at their Bailundo headquarters in Angola during a brief pause in the long civil war) to find that we share many of the same objectives and can agree on common strategies.

The best memorial for the 250,000 Somalis who died of famine, the 300 Eritreans and Ethiopians who drowned off Lampedusa and the 70 people who lost their lives at Westgate, would a commitment by all those engaged in conflict – even if they cannot agree on everything - to do all within their power to reduce the vulnerability of their people to hunger.

Andrew MacMillan*

(October 2013)

* Andrew MacMillan is an agricultural economist specialised in tropical agriculture, former Director of FAO’s Field Operations Division. He recently co-authored a book entitled “How to End Hunger in Times of Crises – Let’s Start Now”, Fastprint Publishing.

Last update: October 2013

-

✴ Back to Opinions

For your comments and reactions: hungerexpl@gmail.com